The protagonist of Graham Greene’s novel The Power and the Glory is an unnamed priest. He lives in hiding during a violent anti-clerical moment in early 1900’s Mexico. All the other priests in his region have left the area, except one who disavowed his vocation and left religious life. Greene’s unnamed priest moves from village to village secretly offering communion in exchange for some contraband – a little drink. The whiskey priest, as Greene calls him, lives on the run. He sounds courageous by that description, but he is no saint. He is motivated by the whiskey at least as much as by the Eucharist. He fathers a daughter but then abandons the girl and her mother. He is complicated and wise and flawed and cowardly and faithful.

Eventually, the police capture the whiskey priest, after narrowly missing him for years. The lieutenant questions his new captive about why he has kept up the chase for so long. Like his colleagues, he could have left the province. He could have married and taken up a new occupation. There were other paths.

“That’s another thing I don’t understand,” the lieutenant said. “Why you—of all people—should have stayed when the others ran.”

“They didn’t all run,” the priest said.

“But why did you stay?”

“Once,” the priest said, “I asked myself that. The fact is, a man isn’t presented suddenly with two courses to follow: one good and one bad. He gets caught up.”

The priest’s response echoes in my head over and over. It has for most of two decades. I return to The Power and the Glory every couple of years just to get to it once more, and the stunning reflections on faith that follow it as the novel winds down. I’ve recently read it once more. In the background, I’ve been thinking about myself, and how my recent work has worked on me.

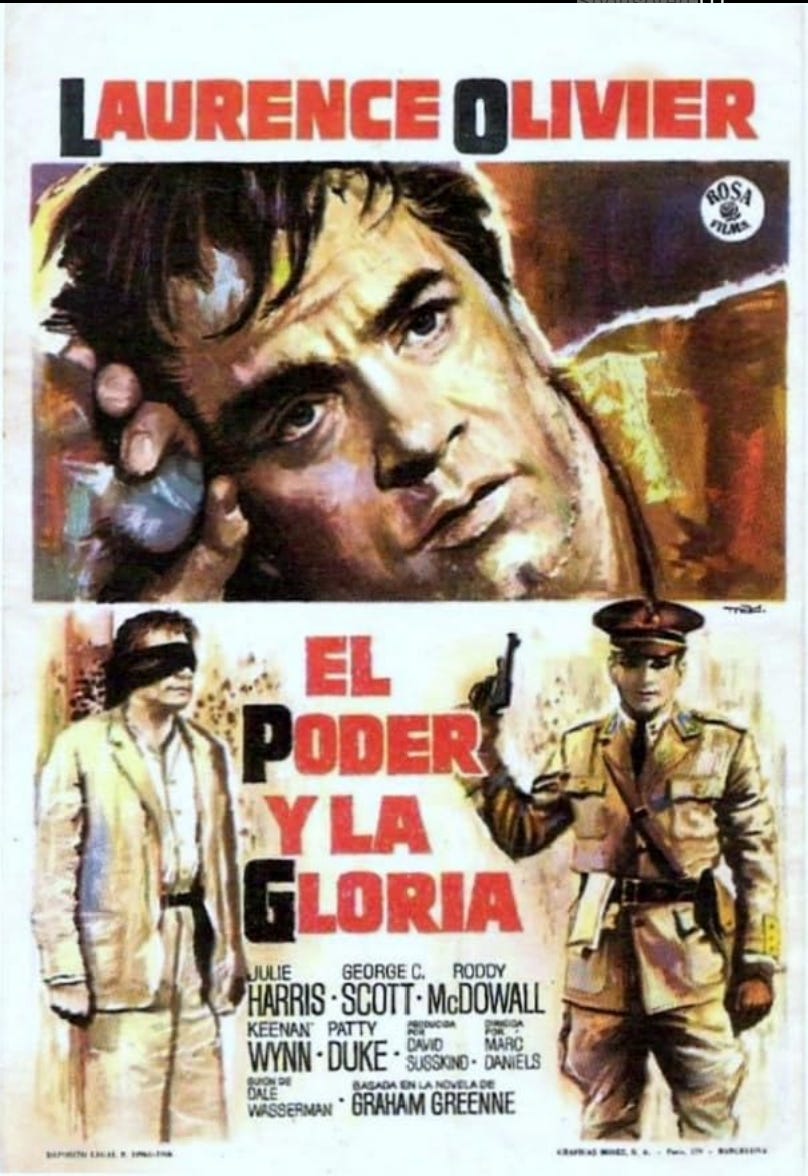

(Above: a movie poster from a 1960 film adaption of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory. I’ve not seen the film.)

Over the past five years, I’ve researched and written and studied intensely about how the Christian faith practiced in white-dominant churches created—and still creates—conditions for the conquest of the world rather than its redemption. I focused on Urban Renewal, but that is just one chapter of a long journey in the same direction. That’s not a small criticism. I’m leveling that charge at the core of the thing that is also at my core.

Along these five years I’ve been thinking and rethinking my relationship to the faith I’ve been writing about. That’s partly mid-life crisis material. I’m fully in the middle of existential angst about vocation and meaning and purpose and what a next chapter might hold. At 44 years old, all those questions are right on time. Lacking the resources to buy a sports car or the desire to have an affair, I’m going the anxiety-filled route, and it is delightful. I haven’t slept in months.

One of the physical spaces that has forced me to think about my relationship to faith has been at First Baptist Church of Charlotte. I was an occasional attendee over the past couple of years for the purpose of research. I walked around the building a bunch of times, inside and outside. Sometimes I was headed to the library or a conference room to bury myself in the archives. Other times I was just taking it in: the familiar stained-glass scene, the sloping sanctuary floor, the brutalism-inspired corridors and indoor plazas. Sometimes I just walked around outside, calling the names of those Brooklyn1 neighborhood residents who used to live on that block.

One of the striking things about the place was how much it felt like home to me, by which I mean, both the congregation I grew up in and the evangelical subculture that surrounded it. But the things that would have connected with me as a youngster fall flat in mid-life, the emotion-drenched music especially. You know the image, even if you’ve never been in the spaces: strummed guitars, singers with hands raised and eyes closed, drums behind a plastic enclosure, lyrics on a screen. Those spaces often receive scorn in popular culture, but on the inside they respond to a deep hunger that shouldn’t be dismissed easily. Whether they rightly fill that hunger, or instead feed a machine of injustice and misdirection, is an important question. Regardless of where you come out on that question, the hunger is real.

There’s a part of me that envies the hunger, the passion, the zeal. And I don’t fully understand my staid response. It is not just about being an insider who knows too much, or taking the dispassionate position of a researcher. If it was that, then the feelings would not persist in a different setting. But I’m also unmoved in the liberal churches where I’m more likely to feel at home today, or in the worship services at the conferences I occasionally attend, or even in the little anarchistic church that I’ve been part of starting. I learned early on to associate Christian spirituality with feeling. Deep feeling. These days, I’m not feeling it.

But I’ve never considered walking away. Well, that’s not true. I think about walking away regularly. I don’t do it because I just cannot imagine anything else. You get caught up.

I’ve yet to walk away because something has hold of me, even when I might let go of it. You get caught.

The language sounds constraining. Being caught, like in a trap. Held, as in detained. The root sense of the word ‘religion’ has to do with binding. Bound, tied up, compelled, seized, captured. You might think it is the language of oppression or control. Indeed, in many places it is. And even when it is not, many people feel that it is. They often throw off traditional religious practice and choose to bind themselves to something else. I get it.

Leaving is not my response, though. I’m still hanging around. I don’t understand that, so I’m just staying curious about it for now. I think of myself being loosely held. Invited, but not compelled. Mostly, I say no to the invitation, but I know it is there. I may yet come back to it.

In the meantime, I keep showing up. It feels hollow, but I show up anyway. You’ve probably heard folks describe themselves as ‘spiritual, but not religious.’ This usually seems to mean that someone wants to hold on to certain spiritual practices, but they don’t want to be held by religious institutions. I understand, kind of, but I’ve become the reverse: religious, but not spiritual. I do not know how to pray. I envy people moved by music in church, but I feel little if anything. Dr. King confesses a faith where “the moral arc of the universe, though it is long, bends toward justice.” I see little reason to believe such a thing. I keep reading the scriptures, but I long ago stopped filling journals with meditations on what I was reading. But what I have, I give: I show up. I go through the motions. I’ll let those across time and space who believe hold me since I cannot muster it for myself.

My work, as I said above, has worked on me. In some ways, it may have pushed me a little further from faith. It also showed me one of the ways I’m still caught up. The stories of faith have a hold on me.

I felt it while writing Our Trespasses.2 As I dug further and further into the research, I needed a story that could contain or make sense of what I was learning. The stories that I know, the ones that formed me, the ones that I always return to, that make sense of this senseless world, are Bible stories. One in particular became the frame—the story of the silencing spirit in Mark 9:14-29.

At the center of the story is the father of a son possessed by a spirit that silences him. No one can heal the boy, so his father brings him to Jesus. The disciples have already tried to exorcise the spirit. They only displayed their impotence. Can anyone help?

“All things are possible for the one who believes,” Jesus instructs the man.

“I believe,” he responds. “Help my unbelief.”

“Charlotte’s Haunted Future”: I’ve taken the work that I’ve done in Our Trespasses and turned it into a walking tour called “Charlotte’s Haunted Future.” Over the course of two hours, small groups walk with me through downtown looking for “stories of exclusions and invisibilities,” in the words of sociologist Avery Gordon. Over the past few weeks I’ve led groups from Caldwell Presbyterian, the national conference of Actionable Intelligence for Social Policy, Providence Baptist Church, and will be leading soon for the staff at Crisis Assistance Ministry. Interested in bringing a group, or joining one? Let me know and we’ll work out the details.

One More Note: The composer Darcy James Argue has a new album out. Argue writes for large ensemble jazz groups (modern “big bands”) and the new work is amazing. The writing is terrific, the soloists are world class, and the engineering is perfect. A superb album. Here’s one of my favorite tracks:

For my readers not local to Charlotte, Brooklyn is an important historic Black neighborhood in downtown Charlotte. The neighborhood was taken and plowed down for an Urban Renewal project. First Baptist became a part of that project.

I’m not sure if you heard, but I’ve written a delightful book that you’re going to want to read. There’s a lot about it in some other posts at my Substack. And you can pre-order it with this link.

I've been wanting to reach out to let you know I had the absolute privilege of proofreading "Our Trespasses." It will stay with me for a long, long time. And I relate to what you write here so much. Loosely held and religious but not spiritual indeed.

Greg, your honest words will resonate with a lot of us. Throughout over 70’years of my life there have been periods of ebb and flow - questions, doubts, disillusionment, buoyant hope, a sense that the Holy Spirit is surrounding me, or an emptiness - like God has given up on me-on us all! Your work is hard and draining. It must seem futile sometimes. Grace and peace to you! Thank you for sharing.