My friend J’Tanya Adams of Historic West End Partners in West Charlotte is always scheming up something good. When she called me recently, I knew I would probably wind up with a project to work on, and it would be a good one. I don’t say “yes” to much nowadays, and won’t until this book is finished (about which, there is big news below…), but there are a handful of people I don’t turn down. J’Tanya is one.

She described to me a new project: a community resource center aiming to serve small businesses and non-profits who focus on serving the west side. The center will have co-working space, commercial refrigerators and freezers for distributing food to people in need, access to shared professional resources, and other services for neighbors to access. J’Tanya has been building networks and systems of neighborhood care for decades, so I have no doubt the hub at 1017 Beattie’s Ford Road is going to be an important space.

I jumped at the chance to play a very small role in the open house because the building already is an important space, historically speaking.

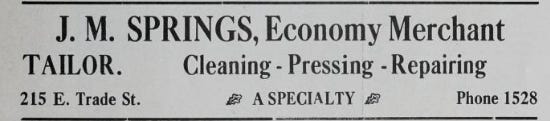

In 1916, Bessie North Springs bought the lot at 1017 Beattie’s Ford and built the house that J’Tanya is now working from. Bessie and her husband Mervin Springs ran a tailor shop downtown, and apparently did a good enough business to purchase their own home.1

1017 Beattie’s Ford is in the Washington Heights neighborhood. Bessie and Mervin were among the first purchasers there, in an area being marketed to upwardly mobile African-Americans.

The Springs’ purchase of the house was a big deal within their family and community. Homeownership around the country was low. In Black communities, subjected to the whimsical cruelties and inane policies of white supremacy, homeownership was even lower. The Star of Zion, the national paper of the AME Zion Church, with headquarters in Charlotte, even printed a note of congratulations for Bessie and Mervin.2

To make the purchase even a little more interesting, Bessie North Springs bought the property in her name, without her husband on the title.

Homeownership was not unusual to her, though. Her parents, Abram and Annie North were among the first Black homeowners in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Charlotte. They purchased a lot at 625 E. 2nd Street in 1893, built a house on it, and moved there in 1896. If you’ve followed along with this Substack, their names might ring a bell. Sixty-five years later, the Norths - the house was then owned by Bessie’s sister Hazeline - became the first Black homeowners forced to sell to the city of Charlotte through the legal and financial framework of the federal Urban Renewal program.

I’ve followed Abram and Annie North around various archives and documents for several years now. Abram had a habit of writing to various newspapers about things that interested him. One stream of Annie’s living legacy persists in the form of Clinton Chapel AME Zion Church, where she was a founding member. The evidence of their lives and work in Charlotte is still here. But in terms of artifacts - tangible things left behind - there is but one piece of evidence I can find. Their Brooklyn house is gone. The former Clinton Chapel church was destroyed in the early 1950s when Duke Power decided they really wanted the property, and no one in the city power structure could think of a good reason to tell them “no.” Searches of attics and church archives have turned up but one thing.

I’ve hoped to locate documents and photos and other objects. After years of study and research done largely on screens, I wanted to see a thing, in three dimensions, that would offer a point of connection. The ancients built altars and reliquaries to house the precious goods of beloved saints. I understand the impulse to do so, for how it preserves real a presence in the world. Reliquaries and photos and portraits challenge the superstition that we live locked only in the present

I went to visit J’Tanya’s project last week. Walking into 1017 Beattie’s Ford, for me, was stepping between realms. I kept looking for the things in the home that were clearly original. The oak floors, in some sections, probably are. The trim around the doors definitely is. So are the bricks in the foundation. Perhaps the plaster on the walls and the ceilings. All of it was a connection, a space shared across time. Other hands built this place, other feet have trod these floors. They nailed the trim above the windows, perhaps, or sanded the plaster down until it was smooth. I’ve read everything I can find about the people who did that, and now here we were in the same room, almost near enough to touch. I closed my eyes and breathed the air and listened to the sounds of my feet on the floor and knew that I was inside someone else’s space, someone else’s story. Neither the space nor the story are “mine” in any possessive sense, and yet by some miracle I get a bit part in it. My part places on me responsibility for my work in the world as a writer, a storyteller, a parent, a neighbor. Part of my responsibility is simply to be in awe. And I am.

Much of what passes for history in American culture - especially among white Americans - is really an attempt to divorce us from our connections to the past, while at the same time re-packaging the past as sentimentality and selling it back to us. It replaces wonder, or respect, or affection, with half-truths in service of hegemonic power. You’ve seen it this week in a manufactured controversy over a Black woman playing a flute. The singer and flautist Lizzo was able to play a crystal flute belonging to James Madison, first at the Library of Congress, and then at a concert. Predictably, the right-wing outrage machine suddenly cared about an instrument about whose existence they were previously unaware. It would have been charming if Ivanka Trump did it, but Lizzo had committed the desecrating sacrilege. The racism of their reaction is so obvious, and so unsurprising, that I’ve wondered if it is worth comment.

Yet, I’ve been fascinated by the newfound obsession with an old flute, and what the reaction might be telling us. The instruments of the past are the only things we have to make the music of the future. We are always surrounded by artifacts and spaces with lives of their own previous to us. Even our own cells are recycled, as though our bodies came from elsewhere by way of sun and soil, and will go back to them. But we are not always aware that we share this world across disjointed time. Every street across this land is haunted with past and future specters, but, as Avery Gordon says, sometimes “we are missing what we are missing.” The performative outrage over the flute was not about the artifact, of course. It was in part about who gets to write songs or tell stories. It was in larger part about the kind of responsibility those stories and their characters will place on us for our own actions. Those screaming the loudest about an old flute desperately want to avoid the responsibility that is ours: to act for the sake of justice.

To be responsible across time is not only to have debts to those before us. It is also to have obligations to those who will follow us. Sentimentality does not preserve the past; it kills the past, and with it the hope of a future distinct from the past. It places us in the tyranny of now, where we have neither antecedents nor successors to make claims on our lives. Perhaps you can live that way for a little while, or at least a few people can, but you cannot be free.

I adore J’Tanya’s work because it so comfortably flows in the disjointed time that is the condition of the world. She did not know who built the house, but neither was she surprised that ancestors who nurtured community and built lasting institutions had previously constructed and occupied that space. Of course they did. And of course she was breathing in their air, and following in their path, and keeping the path clear for another generation. That’s freedom.

If you’d like to see the space, it will be open to the community Sunday, October 2 from 5-7pm. Dawn Anthony and I, and our band Carolina Social Music Club, will be playing for the event.

Update (10/3): The open house was terrific. Occasionally there are gigs where you show up for the job because you have to, but you really don’t want to. That was this one for pretty much everyone in the band it seemed. And then, from the downbeat, the room nearly exploded with energy. Most fun in a while. You can tell from the picture below - that note must have been so good I had to jump up on my tiptoes.

Thanks to J’Tanya Adams, Historic West End Partners, the food vendors, and my musical colleagues Dawn Anthony, Lovell Bradford, Lovell Bradford, Jr., and Malcolm Charles for a great night.

And now for some exciting news:

You probably landed here with some knowledge that I’ve been working on a book about the religious history of Urban Renewal. If you’ve been around me in person, you’ve doubtless heard me drone on about it without end. You can read the other posts in this Substack to get a little more info, or invite me to a cocktail party to get a lot more info.

The book is now under contract with Fortress Press. I’ll spend another six months or so finishing and revising the manuscript. You’ll see it sometime around the end of 2023 or beginning of 2024 with the (for now) title Our Trespasses: White Churches and the Making (and Taking) of Neighborhoods.

Fortress is one of the finest theological presses in the world, with a catalog that includes important titles like this and this and this. I’m excited to be working with the team there.

Final Note: I wound up with a few complimentary tickets to hear Arturo O’Farrill and the Afro-Cuban Jazz Ensemble this week, and I was blown away. The arranging, the soloists, the incredible percussion: everything was locked in. Here’s a piece from the ensemble.

The two advertisements pictured below come from the 1915 pamphlet Colored Charlotte: published in connection with the fiftieth anniversary of the freedom of the Negro, housed in the archives of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Available online here. I learned of this pamphlet from Dr. Tom Hanchett in his book Sorting Out the New South City (references here from pp. 140-141). Tom has been a good friend to me and to this project.

Hanchett cites this in the book mentioned above. My thanks to Mike Moore, the finest researcher I know, who helped me put the pieces together. Star of Zion, 8 June 1916.

Waiting with much anticipation for this next book!! On my list already. With deep appreciation.

As always...thankful for you