[This post, and some occasional posts going forward, is by a dear friend and brilliant scholar, Dr. Joseph Ewoodzie. “Piko", as friends call him, is a sociologist who studies and writes about belonging. His current work is on migration and the ways that immigrants sacrifice and then re-create belonging in both systemic and intimate ways, alongside the ways they are shut out of belonging. I will return later this week with some further thoughts from my recent book tour— GJ.]

Two pictures have been on my mind lately.

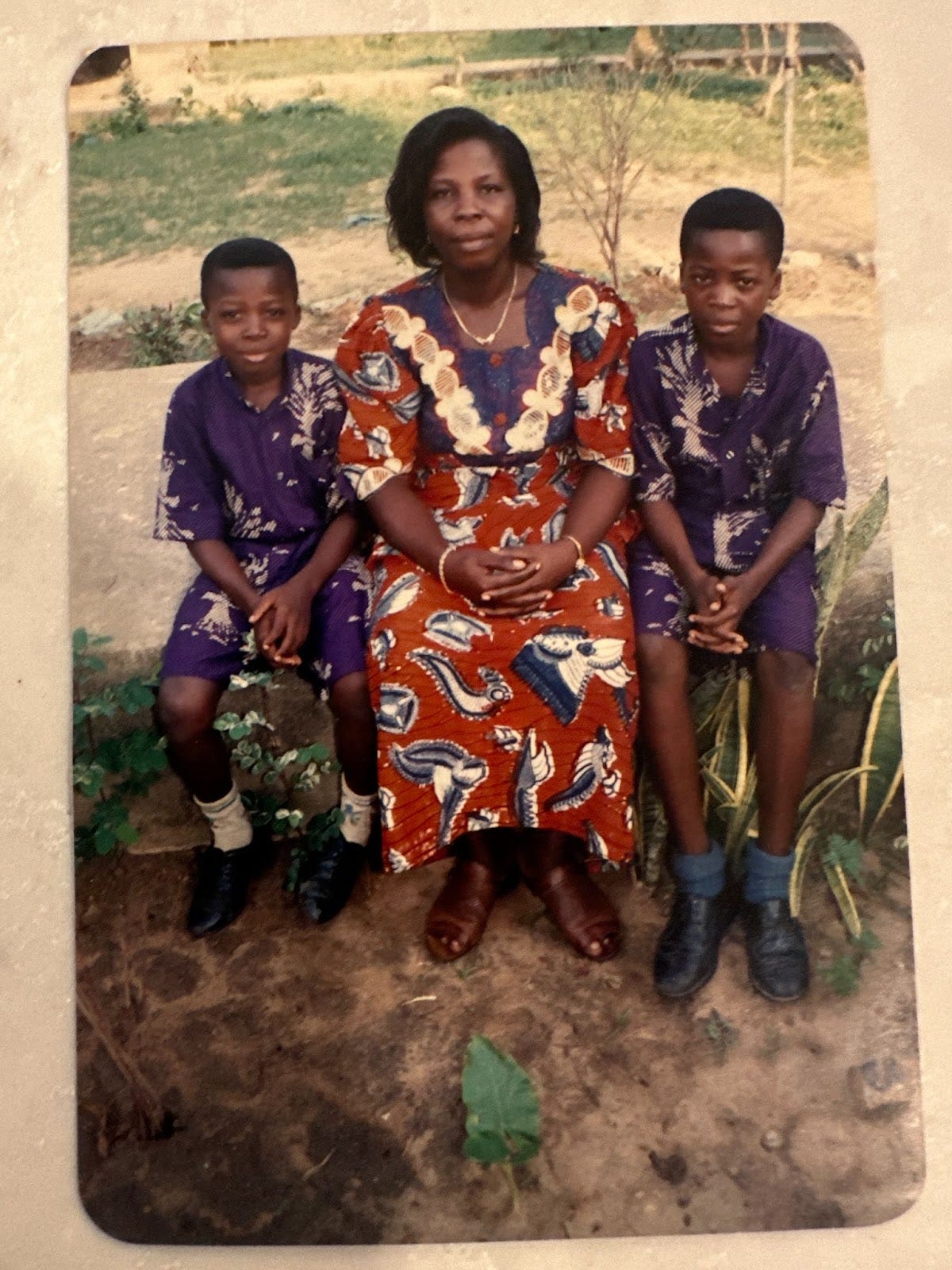

Here’s the first photo.

That’s me sitting to my mother’s left. You can tell that I had just wiped my tears. My mother is faking a smile, and my brother, who I have learned over the years, processes his emotions much differently from me, and has a more genuine smile. If memory serves me right, this is the last photo we took before my brother and I emigrated from Ghana. I am certain that the clothes we had on were the same ones when we stepped off the plane in New York in 1997. My father probably took that photo. He and my mother were divorced so when he came to take us to America (every Ghanaian child’s dream) we were leaving my mother behind (every child’s nightmare).

Here’s the second photo.

I’m a father and a husband in this one. The bags were piled on the side of the front door because we were getting ready to leave our home. Our neighbors across the street snapped a few last-minute photos of us as we waited for our Uber to arrive. If you zoomed in, you’d see that my wife was holding back tears. I had my shades on to cover it up. When we got into our Uber van, none of us could hold it back any longer. We all cried, my wife, our teenage daughter, and I. The toddler also probably cried because we were all crying. The driver, a kind black woman, asked and we explained that we were crying because we were leaving our home.

These two photos were taken 27 years apart. So much has changed in my life between the two. And I’ve moved several more times, both nationally and internationally. But I remember having the same feeling in the photos. I remember feeling that I was leaving a place where I belonged.

I have been reading a lot about belonging. Doing that work has helped me understand how I was feeling in these photos. Belonging is an everyday word that has come to carry analytical significance for various social scientists, including migration scholars. As a concept, it offers a way to study the need, the seeming natural need, to feel attached to people and places. Most writings about belonging can be organized under two main umbrellas: the structured and public dimensions of belonging or the personal and intimate dimensions of belonging.

In the public domain, belonging, or what some have termed “the politics of belonging,” is the “dirty work of boundary maintenance” (Antonsich 2010, Yuval-Davis 2006). At this highest scale, scholars often focus on maintaining boundaries at the national level. The politics of belonging centers around questions of citizenship, institutions, policies, and ideologies that determine who is included and excluded in a nation.

I don’t know what it means to belong to a nation. I was too young when I left Ghana to have a national identity. That thirteen-year-old probably assumed he was Ghanaian, but what did it mean to him? At the very least, he took that national identity for granted. I didn’t come to a sense of thinking of myself as Ghanaian until I became a U.S. citizen two weeks before I turned 18. At the naturalization appointment, I had to take the oath of allegiance. Oddly, I became aware of my national belonging when I had to trade one for the other. Like many other migrants, I traded the one endowed to me by birth for one the one our host country, (in this case the U.S.) reluctantly gives to us.

Belonging in the public domain isn’t always at the national level. When I lived in Charlotte, I always felt safer when I pulled into my neighborhood. Whether real or imagined, that sense of safety made a difference to me. My tense shoulders relaxed. It was almost as if the streets that made up my neighborhood were out of the Charlotte- Mecklenburg Police Department’s jurisdiction, or that of any police department, for that matter. Hyde Park Estates was home because it was built for me. Developed in 1962 by Dr. Charles W. Williams, Hyde Park was one of many responses to Urban Renewal. According to oral histories from neighbors and elders, the development had in mind black middle-class Charlotteans who were displaced from McCrorey Heights by the construction of Interstate 77. In fact, four of the homes in Hyde Park were moved to make way for Brookshire Freeway. My neighborhood was a response to the displacement that Black folks in Charlotte and in many other cities across the country faced.

Under the personal and intimate dimension of belonging, researchers examine the emotions of belonging. Even in its everyday use, belonging is often thought of as a “feeling.” Emotions connect and disconnect people from one another. As such, emotions can be gravely consequential and related to the public and structured dimension of belonging. They can be inclusive (belonging), as in the way human rights activists imagine the world, or exclusive (not belonging), as in the way right-wing nationalists imagine the world (Wright 2014, Carter and Merrill 2007, Nordberg 2006, Hughey 2012). Inherent to this, belonging, as an emotion, is at once private, personal, social, and communal. They exist as such in a circular nature (Ahmed 2004). The private and personal gain value and power through their affirmation by the collective and vice-versa.

My sense of belonging in Charlotte hung much more on this private and intimate dimension. Our home in Hyde Park is the second of two homes designed by Harvey Gannt, who was denied entry to Clemson University five successive times until a federal court intervened. (Listen to this clip announcing his victory.) Gantt became the first Black mayor of Charlotte. He designed it for his dentist, Dr. George T. Nash. I woke up every day feeling honored to live in that house. The house belonged to us but honestly, I spent most of my time there making sure we lived up to its legacy. Once, a man pulled up to tell me that he had held his high school graduation party in that house. Another person told me they had their wedding rehearsal dinner there. Dr. Nash was just that generous. There were numerous other stories like that.

We had to share the house just as Dr. Nash had. And we did. We gathered there to eat and drink and listen and learn as often as we could. Musicians played in our living room and front and back yard, chefs cooked in our kitchen, food trucks used our driveway, and a muralist painted our back wall. We held friendly and sometimes tense conversations about housing, migration, citizenship, and faith with rappers, pastors, real estate agents and developers, cardiologists, community activists, and teachers–pretty much anyone who accepted our invitation to join us. We held gatherings with just a few people and gatherings that brought nearly 100 people to our house on one occasion. The more people came to our house, the more we shared that personal space with others, the more it became a social and communal space, the more we felt that we belonged to the house as much as it belonged to us.