This essay was published by the Journal for Preachers in their Advent 2024 issue. Thanks to my colleague Rev. Dr. Jessica Patchett of Madison, WI for soliciting and publishing the essay. If you’ve read my book or been on my walks, the first half of this essay will be familiar and you may want to skip down to the second half.

On a bright Sunday morning in November 1960, Vernon Sawyer walked up the steps into Friendship Baptist Church. Sawyer, who was white and Catholic, was an unlikely attendee at Friendship, the most prominent church in Charlotte, NC’s most storied Black neighborhood, called Brooklyn. He came this day in his professional capacity. Sawyer was the executive director of the Charlotte Redevelopment Commission. The city of Charlotte, empowered by the state of North Carolina and funded by the government of the United States, employed Sawyer to head the city’s Urban Renewal projects. The first of those projects was set to plow Charlotte’s Brooklyn neighborhood to the ground. Sawyer’s crews would raze more than 1,000 residences, displacing several thousand people from the cultural and economic center of the city’s Black community.

Friendship Baptist was the most prominent of the twelve congregations inside Brooklyn. Their veteran pastor Rev. Coleman Kerry, Jr. shepherded a community that reflected the contradictions of life in the Jim Crow South. His people were business owners and day laborers, people of high status and low. Inside their neighborhood they could find nearly everything they needed: schools, churches, doctors, dentists, auto shops, a YMCA, restaurants, grocers, laundries, and at the end of life, a funeral home to prepare their bodies for the earth. Some lived in fine old houses in good repair. Too many lived in shotgun shacks where they were subjected to winter cold and blistering summers in leaky structures run by exploitative landlords. The people of Brooklyn forged a complex place where some blocks were thriving and others barely hanging on, but where everyone had a place. Even when the neighborhood flourished, though, every space faced the limitations imposed by Jim Crow. But when the genteel forces of white supremacy–good Christians like Vernon Sawyer or soon-to-be Mayor Stan Brookshire, a Methodist–looked at the intricate mosaic of Brooklyn, they saw something simple. The place was a slum, every inch of it, and was best suited for slum clearance and the redistribution of its land.

When Sawyer arrived at Friendship that Sunday morning, he would have been greeted with the same welcome that any visitor receives, even to this day. At the door was a man in a black suit, a starched white shirt, and a thin black tie. His nameplate read “DEACON.” He extended a white-gloved hand to Sawyer and the reporter and photojournalist trailing him. “Welcome to Friendship,” he said, containing his surprise at the unexpected crew entering for worship.

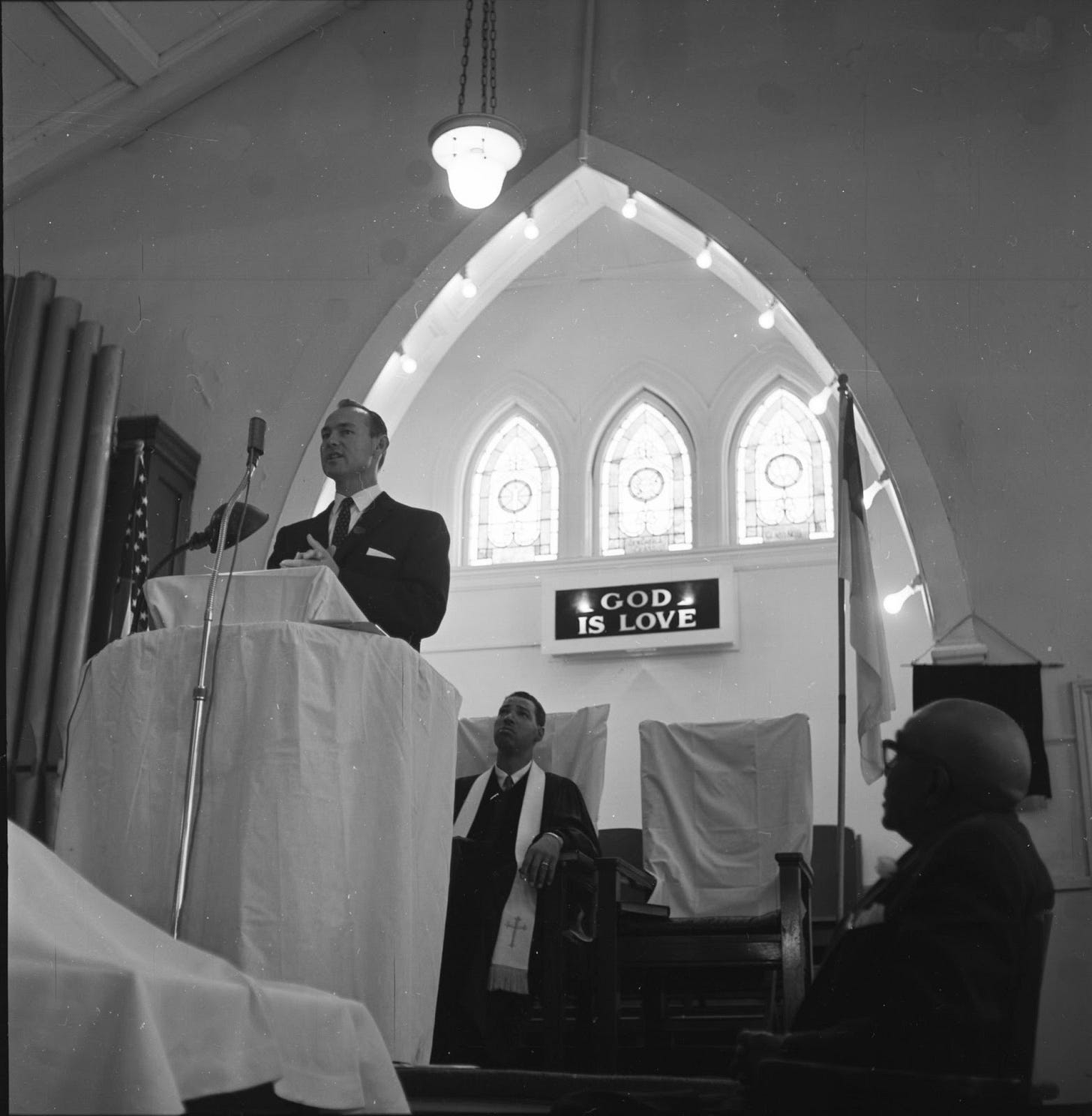

It was a communion Sunday. The table of the Lord had been set in the sanctuary, then draped with a bright white cloth. Pastor Kerry had prepared a sermon for the day, but Sawyer rendered it unusable even before the body and blood had been shared. He commandeered the pulpit for his unannounced visit and delivered a word for the morning: The city of Charlotte has determined that your neighborhood is blighted beyond repair. We believe it would be better used for other purposes. We are taking and razing all 238 acres of the Brooklyn neighborhood, including this property. “The time is getting late to make plans to rebuild your church,” Sawyer said.

Sawyer’s words, like the man himself, arrived as a surprise. At Friendship, they did not know. No one had said, not out loud, anyway, that all across the neighborhood beloved sanctuaries and Sunday School classrooms would face the wrecking ball. City leaders had communicated plainly that all of the residences would come down. Nothing had been said of the 200-plus businesses, the dozen churches, the two schools, all the little sacred corners and blackberry vines and oak trees that were altars of resistance and grief and joy unspeakable. In fact, local opposition to Urban Renewal in Brooklyn had specifically cited the concern that the institutions of the neighborhood would have a hard time surviving if the thousands of people who patronized them were all forced to move. There’s no record showing that Sawyer and company countered the conception that only homes would be torn down.

From the pulpit that morning, Sawyer thundered down an apocalyptic promise to destroy the sanctuary. He knew his words would be unwelcome, so he offered a theological justification to go with them: “Without trying to sermonize, I’d like to point out one thing. Somewhere in the span of endless time, it was you who were chosen to lead in solving this problem at this crucial hour…. The challenge is before you.”

God was working in the world, Sawyer was telling them, and God’s choices in Charlotte required Friendship’s torment. Their suffering had been divinely appointed. Sawyer reframed it to them as opportunity. He used the language of “chosenness” to communicate the coming destruction. He could assume that they would find the language of chosenness familiar, even as he upended its meaning. A century and more prior, the ancestors of the members at Friendship had heard good news in the story of the election of the people Israel and their rescue from the house of bondage in Egypt, even though it was their enslavers who told them the story. They had walked with the liberating God into freedom, had built themselves a neighborhood and a sanctuary.

Now the city of Charlotte and its representatives were undamming a cascade of inverted theological and biblical images. Friendship’s “chosenness” was not for the life of the world, but merely a head fake aiming to distract from the massive land grab the city was running and the federal government was funding. When their building came tumbling down several years later, the Observer featured a photo of a pile of bricks heaped across a bare landscape. The photo told the mixed-up tale of Joshua and Jericho over again, this time turned on its head. Even the name of the federal program, “Renewal,” echoed with theological meaning. The word was as likely to be heard in a sanctuary or Sunday School class as anywhere else, save perhaps a magazine publisher’s office. You might hear it alongside words like regeneration or rebirth. To renew was to bring newness of life. Renewal as policy was fully tragedy to some, but to others it was the miracle of God’s work in the world, an example of God’s providence sorting out things for good within American cityscapes. The newspapers trumpeted its providential nature in homes and businesses, while Charlotte’s best white progressive preachers proclaimed it so from their pulpits.

Nationwide, “renewal” renewed nothing. It displaced millions–so many that ⅔ of the way through the program, the federal government stopped counting. Its lasting legacy includes urban areas carved up by expressways, the ecological devastation of suburban sprawl, the spatial reinforcement of racist ideologies written into our city maps, the massive transfer of wealth from politically weak populations and institutions to politically dominant ones, and parking lots. So many parking lots. The story of urban renewal has not ended. We still live inside it.

Pastor Coleman Kerry, stunned by Sawyer’s brash visit, attempted to gather his flock. He called for them to return that same afternoon for a congregational meeting. Kerry tried to rally his congregation: “How many of you would like to do the impossible? How many of you, within the time limit, would like to see us have enough money to build and to operate, and to meet the challenge of the future?”

The people of Friendship responded by rising to their feet. There was no choice but to do the impossible. They would have to turn their world rightside-up yet again, this time facing an army of bulldozers and bureaucrats.

The Revised Common Lectionary begins each church year with Advent readings of apocalyptic devastations. In year A, Jesus promises surprising disappearances: “Then two will be in the field; one will be taken and one will be left. Two women will be grinding meal together; one will be taken and one will be left. Keep awake, therefore, for you do not know on what day your Lord is coming” (Matthew 24:40-42).

In year B, Jesus points to coming ecological collapse. At the great unveiling, “the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken” (Mark 13:24-25).

In year C, Luke’s Jesus warns that on the earth there will be “distress among nations confused by the roaring of the sea and of the waves. People will faint from fear and foreboding of what is coming upon the world, for the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (Luke 21:25-26).

Across all three years, the readings for the first week of Advent come from Jesus’ teachings to his disciples about what is going on behind the veil. What sense can we make of a world of unrelenting suffering? Where is the God who will act to bring it to peace? The texts echo the questions of Jesus’ followers in the decades after his death regarding how to interpret the political and religious context around them. How should we work through enmity with our neighbors, or even with the very earth?

The First Week of Advent readings don’t grab the start of Jesus’ apocalyptic messages to his disciples, but the warnings from earlier in those discourses echo into the text anyway. “Do you see these great buildings?” he asks. “Not one stone will be left here upon another. All will be thrown down” (Mk 13:2). When God rearranges the world, Jesus is saying, the spatial and the architectural will undergo a renovation project. The very foundations of our settlements and cities will be shaken, built as they are on segregation, enclosure, discovery, commodification, profit. The renewal to come will be quite unlike the American Urban Renewal program, symbolized by a bulldozer and a commandeered pulpit. In the US, the program was a land grab by powerful people against the politically weak. It was the exercise of domination in a system engineered for exactly that.

The apocalyptic texts that begin the year prophesy an end to hegemony. They promise to do away with the land grab, the commandeered pulpit, the wrecked sanctuary, the political work of turning Christian against Christian, preacher against preacher, neighbor against neighbor. But they begin with destruction. The devastation will not be the re-inscription of domination systems into our landscapes and cityscapes. The renewal to come may be terrifying, but it is also hopeful. In a time of upheaval, it is not some temporary stillness that human communities seek. The construction of pleasant facades will not repair the foundations. Everything must undergo the shocks of disruption. The other texts that frame the first week of Advent look to a promising future–swords beaten into plows, the heavens torn open, the peace of our cities. But first, destruction. The painful inversion of the world’s politics is the promise of God.

As the season progresses, the texts continue to birth surprises. The stories have become familiar, yet year after year they retain their ability to rouse complacent souls from their slumber. An old woman births a fierce prophet. A young peasant woman says a courageous “Yes”; her husband-to-be follows her lead. Shepherds. Star chasers. In these luminous nights, we have a story to match our hopes that “nothing will be impossible” (Lk 1:37). In confounding times, we have a song that relishes in the great inverting God who keeps on surprising the world by “scattering the proud in the thoughts of their hearts, bringing down the powerful from their thrones, lifting up the lowly, filling the hungry with good things, and sending the rich away empty” (Lk 1:51-53).

Once more, God renews the year. Whatever the results of a long fall and a bitter election have been, the debris of our society will surely be piling up across blocks and blocks, even miles and miles. There is nothing new under the sun. This wide country has long been scattered with detritus that cannot turn to compost, only to barrenness. [note: this essay was written in the summer. November’s disastrous election results are now well-known.]

Advent always proceeds through wreckage. Some destruction is not merely death chasing death. Sometimes God clarifies, provokes, purifies, turns the world rightside-up again, even when the politics of domination threaten to collapse our neighborhoods, even our churches. It may yet be that across a bleak midwinter we can lay a new foundation.

Exciting New Review: Christian Century published a terrific review of Our Trespasses in their December issue. Read the review online here.

One Last Note: Keep it zany for yuletide with the Matt Wilson Tree-O.